What Is Foreign Insurance Tax and Who Has to Pay It?

A surprising number of U.S. businesses pay for insurance coverage that is technically “offshore” without realizing it, until a lender, auditor, or new investor asks a simple question: “Did you pay the foreign insurance excise tax?” If the answer is “I’m not sure,” you are not alone. This tax is easy to miss because it is not reported on an income tax return. It is an excise tax reported on Form 720, and it can quietly add thousands (or millions) to the real cost of risk.

What Is Foreign Insurance Tax?

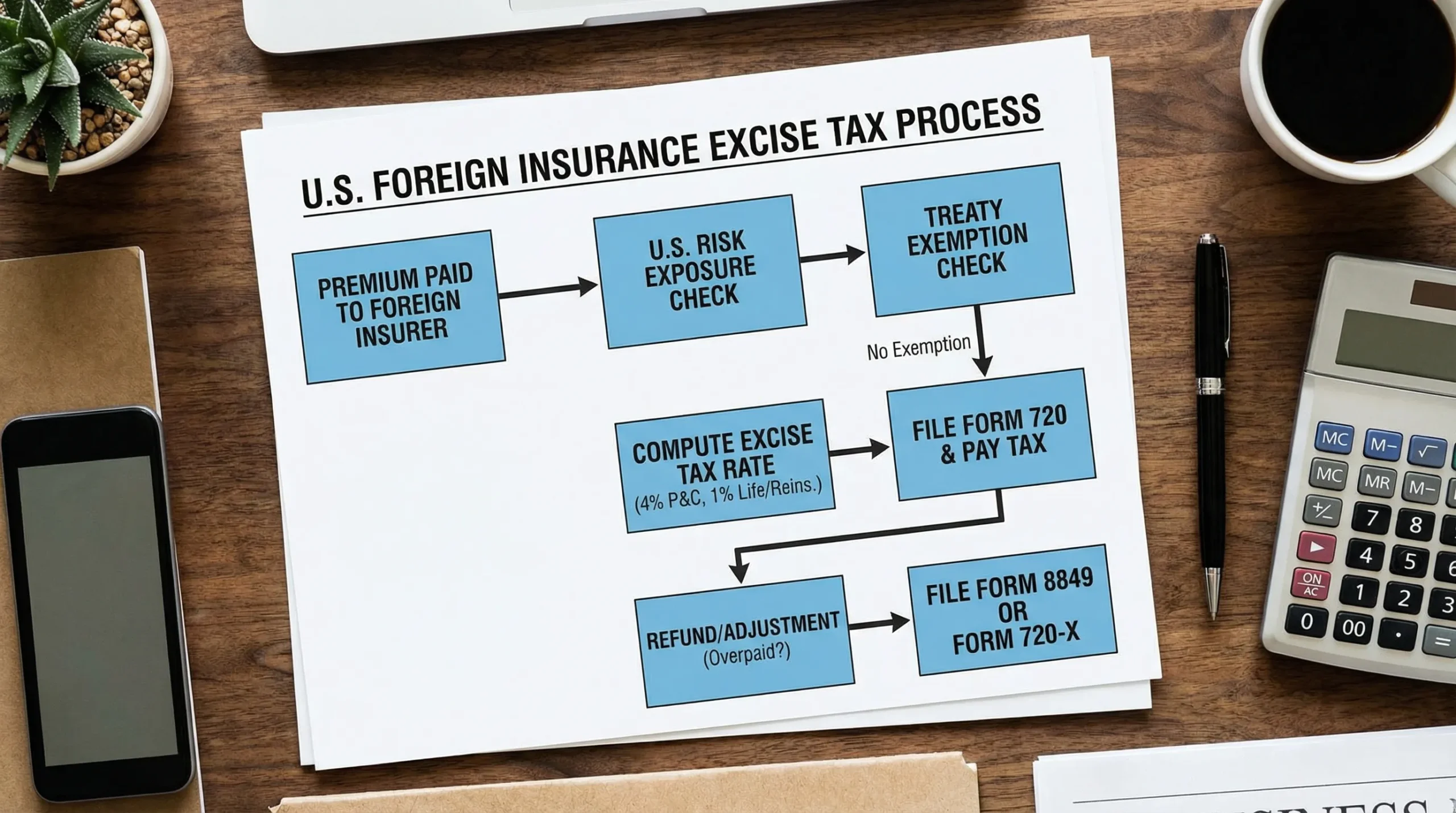

What Is Foreign Insurance Tax usually refers to the federal excise tax on insurance premiums paid to foreign insurers or foreign reinsurers for coverage of U.S. risks. It is imposed under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 4371.

This is not a “tax on foreign companies” in a general sense. It is a transaction tax on the premium payment when the insurer (or reinsurer) is foreign, and the policy relates to risks in the United States.

For the authoritative legal language, see IRC § 4371 and the IRS Form 720 resources.

Why it matters more in 2026 than it did a decade ago

Several trends make foreign insurance tax a bigger practical issue today:

- Specialty coverage growth (cyber, D&O towers, transactional risk/warranty insurance) often involves international markets.

- Captive and reinsurance structures remain common in mid-market risk financing, especially in groups backed by private equity.

- Cross-border program design is more frequent as companies expand globally, sometimes placing coverage with non-U.S. carriers for operational simplicity.

The result: more U.S.-based insureds are exposed to foreign insurance tax, even when their day-to-day broker relationship feels entirely domestic.

Foreign insurance tax rates (and how big it gets, fast)

Foreign insurance tax is typically discussed in three buckets (confirm the exact classification for your policy):

| Premium type (high level) | Common description | Typical excise tax rate under IRC § 4371 |

|---|---|---|

| Property and casualty (P&C) | General insurance against U.S. risks (liability, property, etc.) | 4% |

| Life, sickness, accident, annuity | Life and health-type coverage issued by a foreign insurer | 1% |

| Reinsurance | Premiums paid to a foreign reinsurer | 1% |

A quick “cost of noncompliance” chart you can use in budgeting

Below is a simple way finance teams model exposure during audit prep or M&A due diligence.

| Annual premium paid to foreign insurer | If taxed at 4% (P&C) | If taxed at 1% (life/health or reinsurance) |

|---|---|---|

| $250,000 | $10,000 | $2,500 |

| $1,000,000 | $40,000 | $10,000 |

| $5,000,000 | $200,000 | $50,000 |

If you are buying a multi-million-dollar D&O tower through a foreign market, the “small” excise tax can become a real line item.

Who has to pay foreign insurance tax?

This is where most teams get tripped up. Practically, payment can be handled by different parties depending on how the policy is placed.

In plain English

If your company (or your insurance structure) pays premiums to a foreign insurer or reinsurer for U.S. risk, someone must generally file and pay the excise tax.

In real operating life (who usually ends up responsible)

- U.S. policyholders/insureds: Often responsible if no one else remits the tax. This comes up when coverage is arranged offshore, through a foreign broker, or through a structure where excise tax handling is unclear.

- Brokers/intermediaries: In some placements, brokers facilitate reporting and remittance.

- Insurers/reinsurers or program administrators: Sometimes they handle it, but you should not assume.

Strategic takeaway: Treat it like sales tax in procurement. Even if a vendor “normally handles it,” your team should confirm it is actually being done and retain proof.

Common scenarios where the tax shows up (and surprises people)

1) “We buy insurance from a U.S. broker, so we’re fine”

Not always. The broker can be U.S.-based while the actual risk carrier is not.

What to check:

- The issuing carrier and its domicile

- Where the policy is issued and delivered

- Whether the policy covers U.S. exposures

2) Reinsurance paid to a non-U.S. reinsurer

Foreign insurance tax is not just for primary insurance. If a U.S. insurer or captive pays premium to a foreign reinsurer, the 1% bucket may apply.

3) Captive insurance and fronting arrangements

Captives and fronted programs can involve foreign reinsurers, retrocession, or offshore captive entities. The tax analysis can become structural, not just policy-by-policy.

4) M&A and investor diligence (a real-world pattern)

In private equity diligence, a common “found money” adjustment is discovering that the portfolio company used foreign markets for years, but never filed the Form 720 excise tax line items.

A typical (non-identifying) diligence example:

A sponsor acquires a U.S. manufacturer with international operations. The target bought specialty liability coverage through a London market placement for 4 years. Premiums averaged $1.5M/year. During quality of earnings, the diligence team flags a potential 4% excise tax exposure.

- Estimated tax: $1.5M × 4% × 4 years = $240,000

- Add potential penalties and interest (fact-specific)

Lesson learned: Foreign insurance tax is often too small for business teams to notice month-to-month, but large enough to matter in purchase agreements and post-close audits.

Treaty exemptions and how refunds can work

Some U.S. tax treaties can reduce or eliminate this excise tax for certain foreign insurers, but treaty application is nuanced and documentation-heavy.

Two practical rules of thumb:

- Do not assume “the carrier is in a treaty country” automatically means “no excise tax.” Treaty coverage, eligibility, and administrative steps matter.

- If tax was paid and later determined not to be owed (for example, a treaty exemption is properly documented), a refund process may be possible.

Where Form 8849 and Form 720-X fit

- Form 720-X: Used to amend a previously filed Form 720.

- 8849 form (Form 8849): Used to claim certain refunds/credits for excise taxes in eligible situations.

Because refund eligibility depends on the exact fact pattern and tax type, teams often coordinate with their tax advisor before choosing the cleanest path. IRS starting point: About Form 8849.

How foreign insurance tax is reported (and why Form 720 matters)

Foreign insurance excise tax is reported on Form 720, the Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return.

This is the same return used for many other excise obligations, which is why it often ends up on the desk of whoever already “owns” excise compliance internally.

Examples of other items that can appear on Form 720 (depending on your business):

- PCORI fee (often casually searched as “PCORI Form,” but it is reported on Form 720)

- Fuel Excise Tax and other federal fuel taxes (common in transportation, construction, agriculture, and fleets)

Strategic takeaway: if your team already files Form 720 for fuel or PCORI, foreign insurance tax can be operationally integrated into the same quarterly cadence, with better controls.

Filing strategy: reduce risk, reduce cost, and stay audit-ready

Foreign insurance tax is one of those compliance areas where good process beats heroics.

Build a “premium-to-tax” control

A simple monthly or quarterly control can prevent years of exposure:

- Pull a report of premiums paid

- Flag payments where the insurer or reinsurer is foreign

- Confirm if tax was withheld/remitted

- Tie the result to your Form 720 workpapers

Decide who owns it: Risk, Tax, or Treasury?

Best practice in larger organizations is shared accountability:

- Risk/Insurance team confirms carrier domicile and program structure

- Tax team confirms classification (4% vs 1%) and treaty posture

- Treasury/AP confirms payment trails and supporting invoices

Pricing: think in “total cost,” not vendor fees

Teams often focus on provider fees and ignore the real financial picture.

A practical comparison:

| Decision | What you pay now | What can cost more later |

|---|---|---|

| Invest in clean filing + documentation | Vendor/service fees and staff time | Avoidable penalties, interest, diligence leakage, audit time |

| “We’ll handle it later” | Nothing today | Multi-year exposure and messy remediation |

If you want to file IRS online and reduce manual errors, an IRS-authorized e-file workflow can help with consistency and proof of filing.

Where “E Eile Excise 720” can help (without adding complexity)

If you are filing or planning to file Form 720, E Eile Excise 720 (eFileExcise720) is an IRS-authorized platform built to streamline excise compliance without software downloads.

Use cases that matter for finance teams:

- E-filing Form 720 for foreign insurance tax and other excise categories

- Handling amendments with Form 720-X

- Supporting claims processes tied to Form 8849

You can review the platform and workflow at eFileExcise720. For cost considerations, rely on the site’s published details on its pricing page (fees vary by filing needs and should be confirmed directly).

Common questions investors and CFOs ask (answered simply)

Do we owe foreign insurance tax if our broker is in the U.S.?

Possibly. What matters is whether the insurer/reinsurer is foreign and the policy covers U.S. risk, not where the broker sits.

Is reinsurance included?

Often yes. Premiums paid to a foreign reinsurer can trigger the excise tax, commonly at a 1% rate.

If we overpaid, can we correct it?

Sometimes. Depending on the facts, you may amend using Form 720-X or pursue a claim using Form 8849, usually with professional guidance.

The bottom line

Foreign insurance tax is straightforward in concept, a percentage of premiums paid to foreign insurers or reinsurers, but tricky in execution because responsibility can be unclear and documentation is everything.

If your business buys specialty coverage internationally, uses captives, or is preparing for fundraising or a sale, treating this as a repeatable Form 720 control (not a once-a-year scramble) is one of the simplest ways to reduce compliance risk and protect valuation.